Memory Structure

The structure

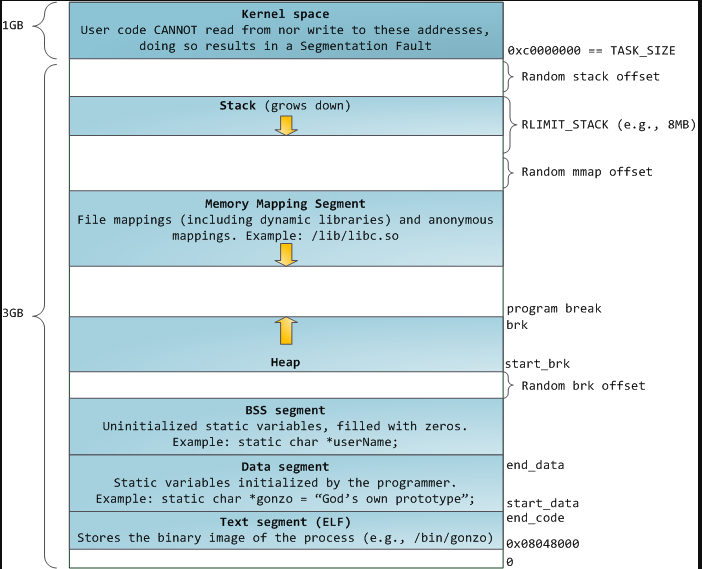

When a program is run by the operating system (OS), the executable will be held in memory in a very specific way that’s consistent between different processes. The operating system will effectively call the main method of the code as a function, which then starts the flow for the rest of the program.

The top of the memory is the kernel area, which contains the command-line parameters that are passed to the program and the environment variables.

The bottom area of the memory is called text and contains the actual code, the compiled machine instructions, of the program. It is a read-only area, because these should not be allowed to be changed.

Above the text is the data, where uninitialized and initialized variables are stored.

On top of the data area, is the heap. This is a big area of memory where large objects are allocated (like images, files, etc.)

Below the kernel is the stack. This holds the local variables for each of the functions. When a new function is called, these are pushed on the end of the stack. The stack grows downward from high-memory to lower-memory addresses. However, the buffer itself is filled from lower- to higher memory addresses. This means that if we would pass a name that is bigger than 100 characters long, it would start overwriting the base pointer that’s lower in the stack (and higher up in the memory).

Buffer Overflow

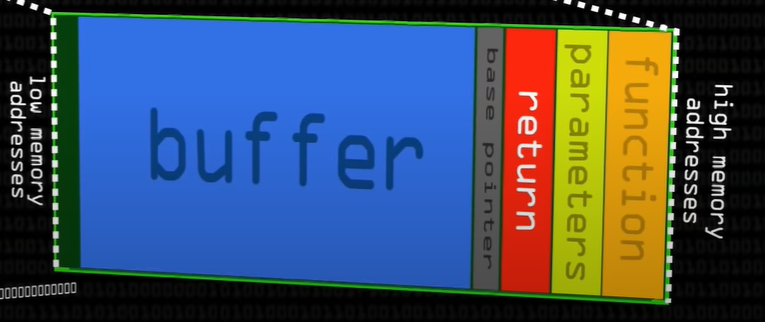

A buffer is a data or memory holding area used to house data. The condition that causes a buffer overflow is when data is exceeding the allocated size of the buffer and thus overflows into other memory areas within the program.

Where these buffers are located will determine the type of buffer overflow attack; either a stack buffer overflow or a heap buffer overflow.

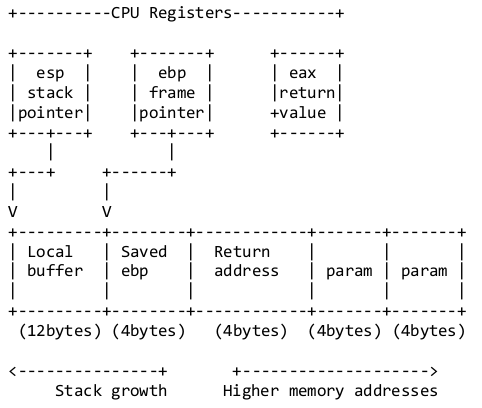

The stack frame contains a return address, local variables and any arguments passed to the function. The return address is used to return control back when the function finishes.

This information is stored in CPU registers; which are small sets of data stores which are part of the processor. Each register is 4 bytes in size

To successfully exploit a stack buffer overflow the return address on the stack must be overwritten.

This is achieved by overflowing local variables within the local buffer in the figure above. Overflowing the local buffer variable will overwrite the return address and create a new return address. This can cause issues when the return address is only partially overwritten and cause the stack to become misaligned. Determining the spacing or offset between the local variable and the return address will aid in keeping the stack aligned.

With the buffer offset determined a malicious payload can be crafted. The payload will overflow the local variable and return address with a different return address and inject shellcode successfully exploiting the program.

A shellcode is a small piece of code used as the payload in the exploitation of a software vulnerability. It is called “shellcode” because it typically starts a command shell from which the attacker can control the compromised machine, but any piece of code that performs a similar task can be called shellcode.

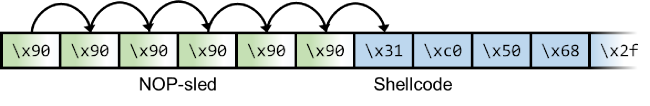

NOP-sled

A NOP-sled is a sequence of NOP (no-operation) instructions meant to “slide” the CPU’s instruction execution flow to the next memory address. Anywhere the return address lands in the NOP-sled, it’s going to slide along the buffer until it hits the start of the shellcode. NOP-values may differ per CPU, but for most OS and CPU is \x90.

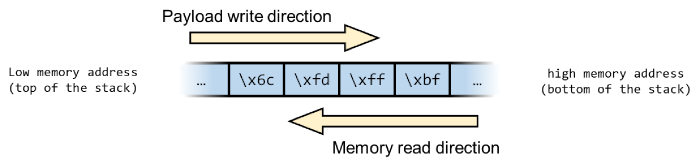

From a memory’s point of view, the payload will be inserted in the buffer from the top of the stack towards the bottom (lower to higher memory). The return address will be read in reverse order, from the bottom of the stack towards the top:

In order for the return address to be read correctly, the bytes need to be written into the payload reversed order, so 0xbffffd6c should be written as 0x6cfdffbf in the payload.

References:

Leave a comment